The management of intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) remains one of the most pressing challenges in obstetrics. Defined as the failure of a fetus to achieve its genetically determined growth potential, IUGR is a condition that not only complicates pregnancies but also predisposes infants to perinatal morbidity, mortality, and long-term health consequences. For decades, the only definitive “treatment” has been timely delivery, often preterm, with all the associated risks for the neonate.

Enter sildenafil citrate, a phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inhibitor better known for restoring male erections and popularized under the trade name Viagra. Its vascular actions—mediated by enhancing nitric oxide signaling and increasing cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP)—have made clinicians wonder whether it could also be repurposed to improve uteroplacental blood flow. Could a pill designed for erectile dysfunction also give struggling fetuses a chance to thrive? This article explores the evidence.

The Biological Rationale: Why Sildenafil for IUGR?

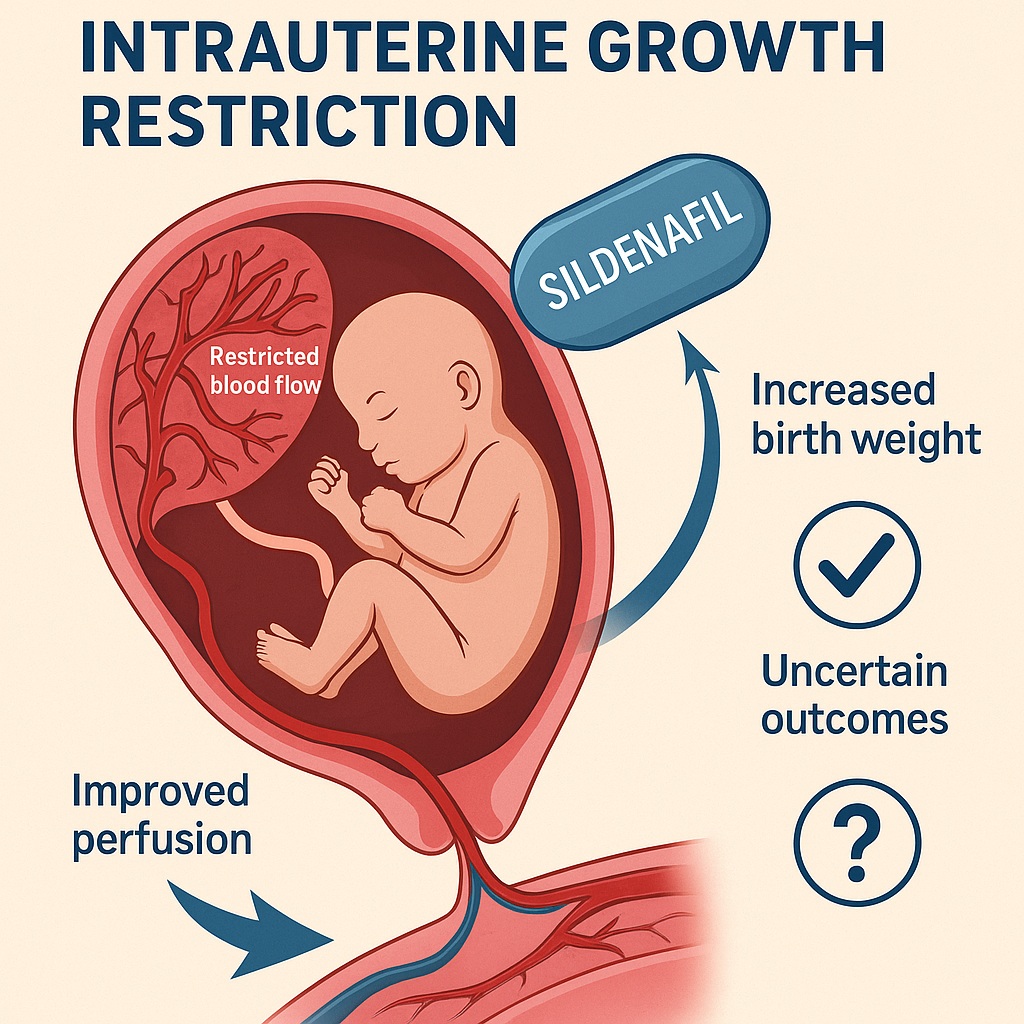

The placenta is the lifeline between mother and fetus, orchestrating the exchange of oxygen, nutrients, and waste products. In IUGR, placental development and vascular remodeling are impaired. Cytotrophoblasts fail to adequately invade and remodel maternal spiral arteries, leaving vessels narrower, higher in resistance, and incapable of delivering sufficient blood. The consequence is reduced perfusion, nutrient deprivation, and slowed fetal growth.

Sildenafil, by inhibiting PDE5, prolongs the activity of cGMP, a second messenger that mediates smooth muscle relaxation. The result is vasodilation of uteroplacental vessels, improved perfusion, and theoretically, better nutrient delivery to the fetus. Animal studies and early human observations supported this mechanism, showing improved Doppler indices and fetal growth velocity. It was perhaps inevitable that obstetricians would test sildenafil in clinical trials.

It must be noted that while the pharmacological logic is compelling, the obstetric context is not identical to erectile physiology. A uterus is not a penis—though both rely on vascular dilation—and the complexity of pregnancy requires far more caution.

Evidence from Clinical Trials: What Do We Know?

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis pooled results from nine randomized controlled trials evaluating sildenafil citrate in IUGR pregnancies. The trials, conducted across different populations including Egypt, the UK, Brazil, and New Zealand, varied in sample size, dosage (ranging from 20 mg twice daily to 50 mg three times daily), and gestational age at randomization. Despite these differences, several consistent themes emerged.

- Birth weight: Sildenafil was associated with a statistically significant increase in neonatal birth weight, averaging about 110 grams more than placebo. For small, vulnerable fetuses, this increment is not trivial; in fact, it may tip the balance between neonatal intensive care survival and morbidity.

- Gestational age at delivery: Data were less convincing. Some studies suggested slightly longer pregnancies in the sildenafil group, but pooled results failed to reach statistical significance. The promise of “buying more time” in utero remains uncertain.

- Stillbirth, neonatal death, NICU admission: Across trials, sildenafil did not significantly reduce stillbirths, neonatal mortality, or admissions to intensive care. In other words, while babies may weigh more, their survival odds were not clearly improved.

This mix of encouraging and disappointing results underscores the complexity of fetal growth restriction and the limits of a single pharmacological intervention.

The STRIDER Trials: A Turning Point

Any discussion of sildenafil in pregnancy must acknowledge the STRIDER (Sildenafil TheRapy in Dismal prognosis Early-onset intrauterine growth Restriction) trials, large multicenter efforts designed to rigorously test the drug’s efficacy. STRIDER-UK and STRIDER-NL produced sobering outcomes: not only did sildenafil fail to improve survival or long-term outcomes, but in the Dutch arm, concerns were raised about potential harm, including increased rates of neonatal pulmonary hypertension.

The trials were halted prematurely, and guidelines quickly shifted to a cautious stance. Professional bodies, such as the Society for Maternal–Fetal Medicine (SMFM), currently advise against routine sildenafil use for IUGR outside of research settings. The initial enthusiasm has thus given way to a more tempered view—useful lesson in the dangers of repurposing drugs without fully understanding their unique context.

Clinical Interpretation: Where Does Sildenafil Fit?

Clinicians and researchers now face a delicate balancing act. On one hand, sildenafil clearly demonstrates biological activity: it increases uteroplacental blood flow and can enhance birth weight. On the other hand, it does not convincingly reduce mortality or major morbidity, and safety concerns persist.

The most prudent interpretation is that sildenafil remains experimental. It may eventually find a role in carefully selected subgroups—perhaps women with particular vascular phenotypes, or fetuses with certain Doppler profiles—but broad use is not currently justified. Ongoing pharmacogenetic and mechanistic studies may yet uncover patient populations who could benefit.

Interestingly, sildenafil has already been repurposed successfully in other areas, notably pulmonary arterial hypertension. This shows the flexibility of PDE5 inhibition as a therapeutic strategy but also reminds us that context matters. A drug that dilates penile arteries with success does not automatically guarantee the salvation of placentas.

Broader Implications: Lessons for Obstetrics and Beyond

The sildenafil-IUGR story carries wider lessons for medicine:

- Drug repurposing is attractive but risky. Sildenafil’s availability and safety profile in men made it a candidate for obstetric trials, but pregnancy physiology is unique.

- Endpoints matter. A modest increase in birth weight is not equivalent to improved survival or neurodevelopmental outcomes. Future studies must focus on what truly matters to families.

- Heterogeneity clouds evidence. Variations in dosage, timing, and patient populations made pooling results difficult. Future research must strive for standardization.

Above all, the story highlights the interdisciplinary nature of perinatal medicine. Obstetricians, neonatologists, pharmacologists, and even cardiologists share a stake in understanding how vascular modulators affect both mothers and babies.

Conclusion: Hope Tempered by Evidence

Sildenafil citrate remains an intriguing candidate in the fight against intrauterine growth restriction. Current evidence suggests it can increase birth weight and may modestly prolong gestation. However, it has not been shown to reduce stillbirths, neonatal death, or NICU admissions. Its role, therefore, remains uncertain and investigational, pending larger, standardized, and safety-focused studies.

For now, the most effective management of IUGR remains timely delivery, careful monitoring, and individualized obstetric decision-making. Sildenafil’s journey from the bedroom to the delivery room illustrates both the creativity of medical research and the necessity of rigorous testing before widespread adoption.

FAQ

1. Does sildenafil help babies with intrauterine growth restriction survive?

Not conclusively. Current evidence shows it may increase birth weight but does not significantly reduce stillbirths, neonatal deaths, or NICU admissions.

2. Is sildenafil safe for use in pregnancy?

Safety concerns remain. Some trials raised questions about possible neonatal pulmonary complications. For this reason, sildenafil is not recommended for IUGR outside of clinical research.

3. Why was sildenafil considered for IUGR in the first place?

Because it dilates blood vessels by enhancing nitric oxide signaling. Researchers hoped this would improve uteroplacental blood flow and support fetal growth.

4. Should pregnant women with IUGR take sildenafil?

No—unless they are part of a controlled clinical trial. At present, clinical guidelines advise against routine use due to insufficient evidence of benefit and unresolved safety concerns.